Immunization: How the polio programme reached every last child in the African Region

The polio eradication programme has been remarkably dynamic: the strategies used have varied between regions, countries and even villages. Adaptation has been vital for success.

Africa’s sheer size, geographic, cultural and linguistic diversity, high levels of insecurity and migration, as well as weak health systems and poor sanitation, are among the unique factors that have shaped the polio eradication response in the region.

These challenges have driven innovation and creativity, says Dr Pascal Mkanda, Polio Eradication Coordinator for the WHO Regional Office in Africa (WHO AFRO). “What has been African has been our innovative way of doing things.”

Vaccinators travel by dugout canoe with cooler boxes of polio vaccines across a lagoon in Adiaké District, Côte d’Ivoire, 2009. ©️ UNICEF

Reaching every child beyond routine immunization

Before mass vaccination campaigns for polio started in the African region in 1996, the only way to protect a child against polio was by way of routine immunization programmes, delivered through health facilities or outreach posts. Although successful, many communities were not easily reached.

To reach more children in under-served areas, polio teams ramped up the delivery of the oral polio vaccine (OPV), along with other vaccines, using a strategy known as ‘periodic intensification of routine immunization’ (PIRI). Teams also conducted periodic outreach and mobile vaccination activities in hard-to-reach places.

In 1996, Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda led the way in polio eradication by implementing supplementary immunization activities, which included national and subnational immunization days, and mop-up campaigns in addition to routine immunization. These mass vaccination campaigns aimed to administer supplementary doses of OPV to each child aged under five years, regardless of whether they had been vaccinated before not.

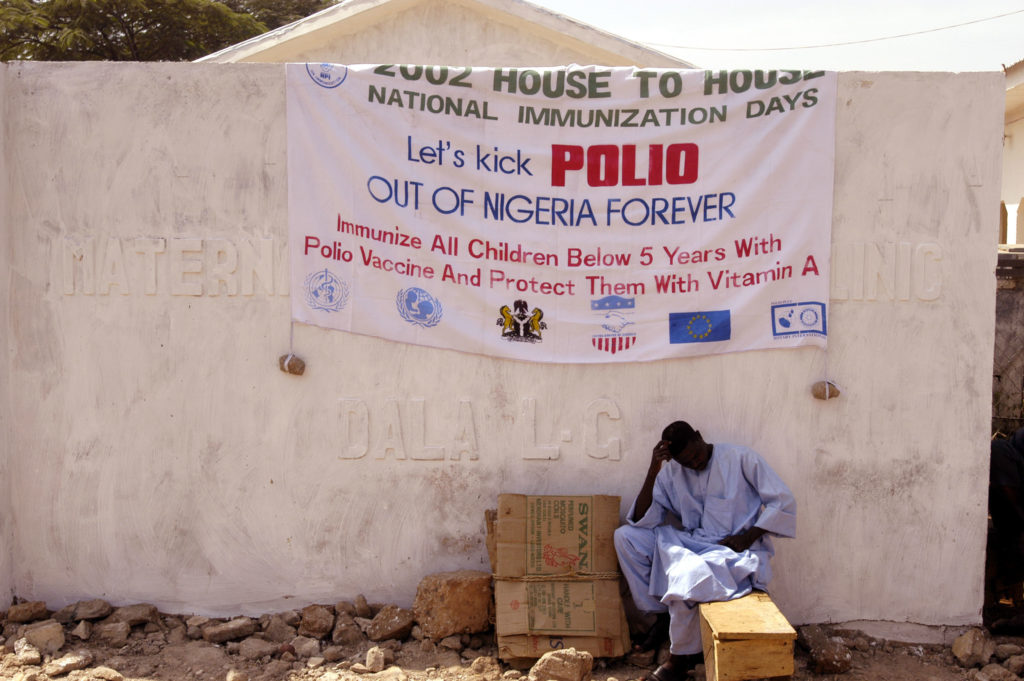

Nigeria was the first country to implement house-to-house campaigns in the early 2000s. ©️ WHO

Reaching children in distant communities

While supplementary immunization activities were first carried out through fixed posts that families had to travel to, starting in 1999 several innovations brought vaccinations directly to children, ensuring even the most vulnerable were immunized.

“Nigeria was the first country in Africa to implement house-to-house polio campaigns,” says Dr Sam Okiror, who has worked with the Polio Eradication Programme at WHO AFRO since the late 1990s. “We immunized 40% more children in 15 states than we were doing using the fixed-post approach.” After this success, he says, “we used house-to-house campaigns everywhere.”

Nigeria was the first country to implement house-to-house campaigns in the early 2000s. ©️ WHO

After initially focusing on national campaigns, polio teams realized that due to Africa’s porous borders, the many people who frequently crossed them were being missed. As such, in 2000, tens of thousands of volunteers and health workers went door-to-door across the entire west and central Africa region, made up of 17 countries, vaccinating 67 million children, including two million who had never been immunized before.

This colossal event marked the start of many synchronized vaccination campaigns: simultaneous mass campaigns targeting millions of children in multiple countries to create enough population immunity to stop transmission across the region.

National and supplementary immunization days across DRC, 2001. ©️ WHO

Kofi Annan, then UN Secretary General, negotiates truces for polio immunization, with mobile teams approaching villages by boat, DRC, 1999. ©️ WHO

Reaching children in conflict zones

In 1999, Kofi Annan, then UN Secretary General, negotiated Africa’s first-ever ceasefire agreement between the government of DRC and rebel forces to allow national immunization campaigns across the country. Since then, numerous cease-fire agreements and conflict-free days, called ‘days of tranquility’ have been negotiated throughout conflict areas to carry out large-scale immunization campaigns.

Where there were no channels for negotiation with insurgent groups, like in Nigeria’s Borno State in 2013, ‘reach every settlement’ strategies were devised. Working with government security, intelligence agents and local groups, windows of calm were identified where vaccination teams were able to quickly enter settlements to vaccinate children and leave undetected.

In conflict areas that were still impenetrable, there was a risk that caregivers leaving with their unvaccinated children to look for food and basic items would carry the virus into surrounding areas. For this, ‘transit teams’ were placed along the routes used to enter and leave insecure areas, as well as markets, nomadic crossing points, check points and border areas to vaccinate children and search for signs of paralysis.

To further stop polio from ‘seeping out’ from the trapped population, using a strategy known as ‘fire-walling,’ polio teams periodically ran ramped-up vaccination campaigns in the areas surrounding conflict zones, creating a ‘wall’ of population immunity.

Female volunteer community mobilizers play a key role in increasing awareness and acceptance of polio vaccines in Kano state, Nigeria, 2019. © Andrew Esiebo/Rotary International

Combating vaccine refusal

Across Africa, vaccination efforts were hampered by pockets of vaccine refusal in the 1990s and 2000s due to rumors and misinformation. In northern Nigeria, however, this became an even bigger issue: in some northern states polio vaccinations were stopped for nearly two years between 2003 and 2004. This unleashed a resurgence of polio cases, which rippled across the country and the rest of the continent, spawning wild polio outbreaks in 20 other African countries.

Vaccine refusal prompted a big shift in communication and social mobilization strategies across the African region, which included building strong links with traditional and religious leaders.

Vaccinators get ready for national immunization days throughout Cote d’Ivoire, using posters, branded t-shirts, helmets and bikes donated by Rotary to publicize the event. © Rotary International

Polio teams started to address other community needs by providing basic household items like soap, sugar or noodles as well as healthcare alongside polio vaccines, which created demand among caregivers for vaccines for their children. Road shows further created visibility and awareness around polio and ‘health camp days’ offered basic treatment during mass campaigns. Teams also worked extensively with networks of religious leaders, Qur’anic schools, women’s associations and motorcycle riders among others to spread messages about polio and build community trust.

Female volunteer community mobilizers play a key role in increasing awareness and acceptance of polio vaccines in Kano state, Nigeria, 2019. © Andrew Esiebo/Rotary International

In some parts, particularly in northern Nigeria, skeptical parents would persuade the volunteer vaccinators moving house-to-house to mark their children’s fingers, a sign they had been vaccinated, without having received the vaccine. These areas continued to face polio outbreaks.

Teams enlisted the help of older children who – in exchange for milk sachets, sweets or whistles – brought younger siblings and friends in the targeted age-group to be vaccinated under observation of senior polio personnel. ‘Directly observed polio vaccination’ reduced the harassment faced by vaccinators and the temptation of vaccination team members to fabricate vaccination rates.

Vaccination teams record polio vaccinations, while offering incentives such as milk sachets, soap, candies and whistles in Maiduguri, Nigeria, 2020. ©️ Andrew Esiebo/WHO

This strategy is believed to have broken the last chains of poliovirus transmission in the most vaccine-resistant communities of Nigeria, where the last case of wild poliovirus in the region was reported in 2016.