How Africa's polio infrastructure supported the COVID-19 response

When 28 year-old John Achuil called the Public Health Emergency Operations Center in South Sudan’s capital Juba reporting COVID-19 symptoms of fever and body weakness, he was rushed into the hospital and tested for the virus. The first responders who helped save Mr Achuil’s life were health workers from South Sudan’s 400-personnel strong polio programme and national Rapid Response Team (RRT) which responds to polio outbreaks, who are now supporting South Sudan’s COVID-19 response.

“I appreciate the health workers who saved my life,” says Mr Achuil, who recovered from COVID-19 after two weeks in the hospital. “I can’t imagine what could have happened to me.”

Mr Achuil is not alone. Across Africa, thousands of people with COVID-19 have been diagnosed – enabling their quick treatment – or spared from catching the virus thanks to the continent’s polio staff and infrastructure.

Across Africa, polio infrastructure and staff are found at district, province, all the way to the national level, so whenever there’s an outbreak, polio teams are always the first to respond.

–Dr Sylvester Maleghemi

WHO Polio Team Lead in South Sudan

The WHO polio team visits the Ambriz border post in Bengo province to provide training on both Acute Flaccid Paralysis (AFP) and COVID-19 surveillance and contact tracing for COVID-19, Angola, April 2020. © WHO

In March 2020, as the COVID-19 outbreak evolved into a global pandemic, the world-wide shift of polio support to the COVID-19 response was swift. The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) immediately redirected the polio eradication program’s staff, assets and funding towards the world-wide response.

In the African region, in particular, the polio eradication program has a long history of responding to other disease outbreaks and health emergencies. With its unmatched technical expertise, disease surveillance and logistics capacities as well as wide community networks, the polio team is perfectly placed to mobilise a large-scale emergency response, while maintaining polio eradication efforts.

“It is very natural for polio staff to take on other health emergencies,” says Dr Sylvester Maleghemi, WHO Polio Team Lead in South Sudan, who has supported the country’s polio and broader immunization programs for years. “Across Africa, polio infrastructure and staff are found at district, province, all the way to the national level, so whenever there’s an outbreak, polio teams are always the first to respond.”

Since April, more than 2000 polio response experts from WHO, UNICEF, Rotary, as well as STOP consultants from the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have been supporting the COVID-19 response across the African region. A quarter of WHO polio staff are dedicating more than 80% of their time towards COVID-19 efforts, with 65% anticipating a commitment of six months or more.

Particularly vital to the COVID-19 response is contact tracing and data management: tools used by polio teams to trace contacts and monitor the spread of the poliovirus have been quickly adapted to trace thousands of suspected COVID-19 cases and help countries take decisions.

“Our biggest strength lies in coordinating daily data collection and managing contact tracing teams. In most countries, contact tracing is being totally managed by polio teams,” says Dr. Godwin Akpan, Data Manager for the Polio Eradication Program at WHO’s Regional Office for Africa (WHO AFRO). His team at WHO AFRO’s Geographic Information Systems (GIS) centre in Brazzaville, Congo, are using their wealth of experience and technical expertise from polio to support countries with a range of GIS and software technologies, as well as manual solutions to respond to COVID-19.

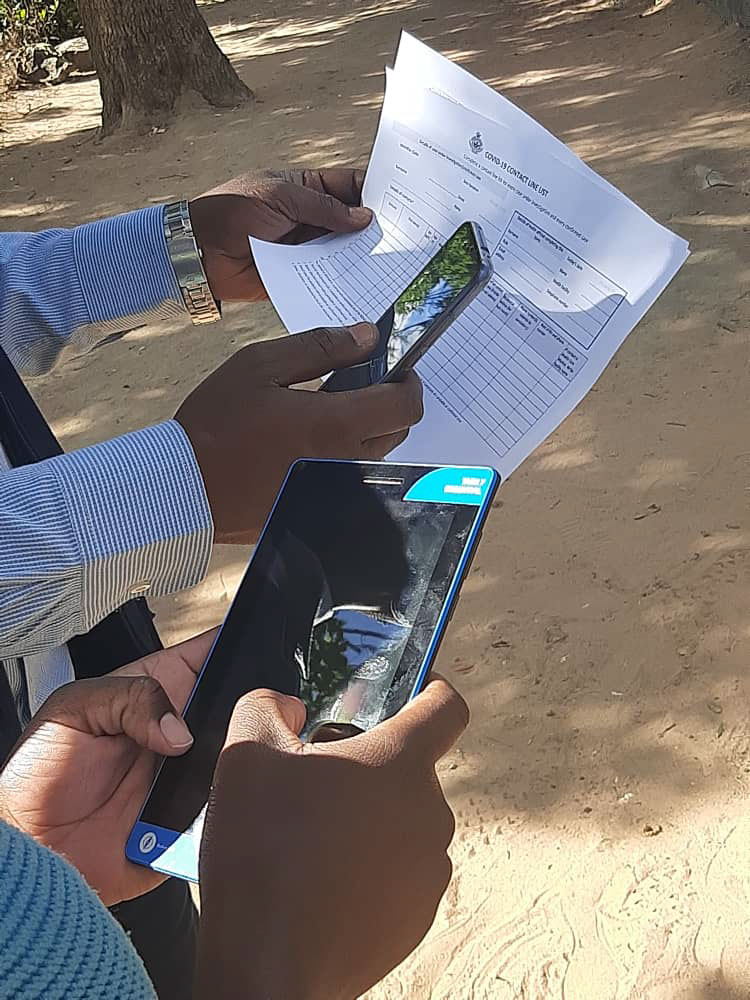

In Zimbabwe, for example, over 100 disease surveillance officers are using a mobile phone application adapted from polio to investigate COVID-19 cases, manage contact tracing and report their findings in real-time.

WHO staff from the Polio Eradication Programme provide training to contact tracers from the Zimbabwean Ministry of Health on the essentials of Covid-19 surveillance and the use of an Open Data Kit (ODK) mobile application adapted to conduct contact tracing and follow up in Chitungwiza, Zimbabwe, June 2020. © WHO

The GIS team are also helping countries develop their own existing apparatuses. “We found that many countries already had their own contact tracing tools,” says Dr Akpan, “so we helped re-engineer their tools and move their data onto dashboards so that the data could be automatically visualised for better decision making.” A crucial aspect has been ensuring that the data is stored securely, respecting data privacy.

In addition to contact tracing, any strategy to stop the transmission of COVID-19 must involve wide-scale testing. “At the start of the pandemic, testing in Africa was low. The African region’s polio laboratory network, which over the last thirty years has evolved to provide strong testing capacities, has helped step this up,” says Dr Nicksy Gumede, Regional Virologist for the Polio Eradication Program at WHO AFRO.

Today, all but one of the 16 laboratories in this network are dedicating 70% of their capacity to COVID-19 testing. Hundreds of tests are carried out every day using polio testing machines in polio laboratories including in Algeria, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Nigeria, Senegal and South Africa. Polio laboratory resources have also been donated to countries with limited testing capacity, without which exact case numbers would not be known.

When measures to curb the spread of COVID-19 were introduced in March 2020, national health authorities across the region suspended polio vaccination campaigns. Yet even as polio’s efforts, assets and funding were redirected into fighting COVID-19, polio teams continued polio disease surveillance activities and planning for future polio vaccination campaigns. With the suspension lifted in May for high-risk countries, polio campaigns were conducted in Burkina Faso and Angola in early July, together vaccinating more than a million children under the age of five.

From providing on the ground support in contact tracing, training and response preparedness, “polio staff are now increasingly supporting decision-making and coordination processes, sitting at emergency coordination centre level,” says Dr Modjirom Ndoutabe, Coordinator of the WHO-led Rapid Response Team for the African Region.

As their role evolves to meet the changing needs on the continent, the region’s polio staff and resources will continue to tackle COVID-19, while pushing to rid the region of all forms of polio and contributing towards universal health coverage. This will be the true legacy of the polio eradication programme in Africa.